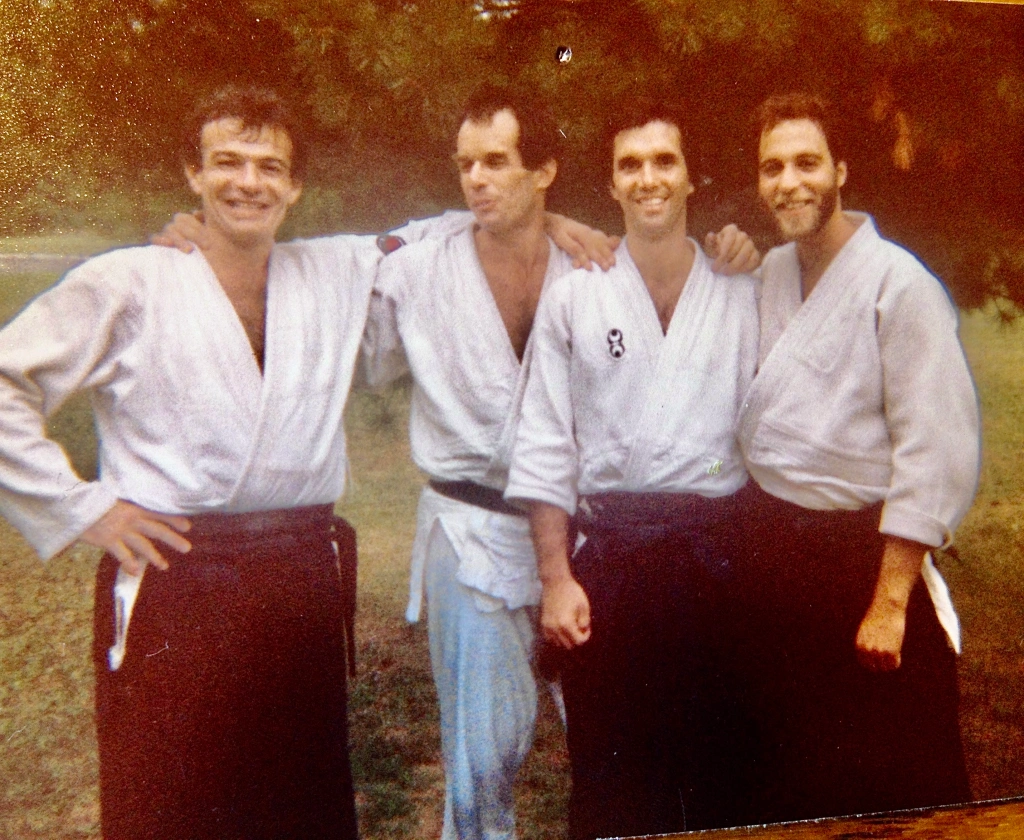

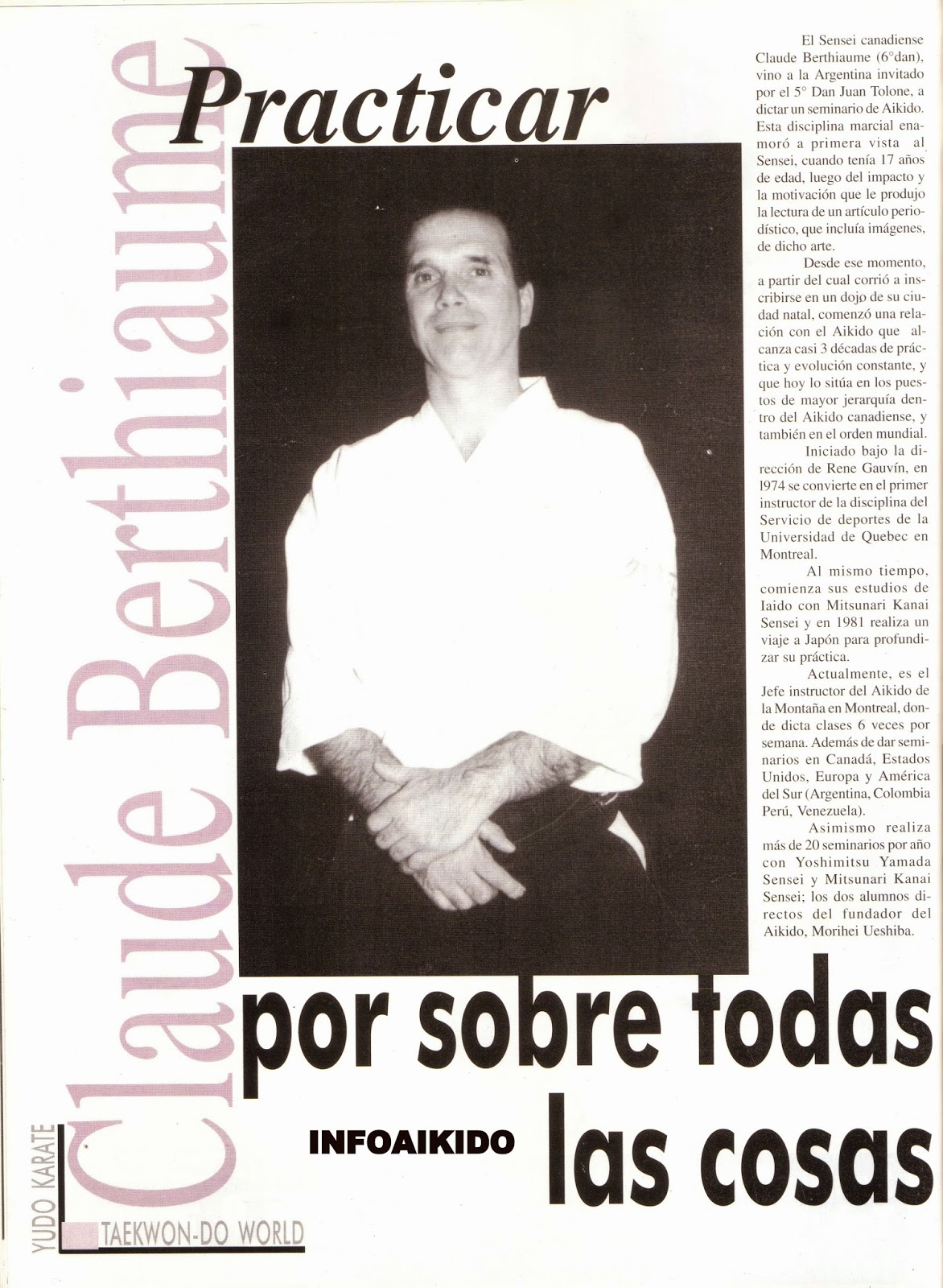

练习53年,教学49年。20年前获颁七段师范,年仅50岁。此前的40年中,北美所有师范均为开祖内弟子。

50年的时间里,保持每周6次出现在垫子上,参加或指导的讲习会超过800场。克劳德老师的合气道之旅,还在继续。

MAYTT: You began training aikido in 1971, at the age of seventeen. What was it that influenced you to begin aikido at the time and does that aspect still inspire you to train today?

MAYTT:你在1971年17岁时开始练习合气道。当时是什么影响了你开始学合气道,这个方面今天仍然激励你练习吗?

CB: Well, in those days I was playing ice hockey and I was not talented enough to become a professional. My brother was doing Tae Kwon Do so I thought I would do the same thing or Judo. I decided finally to go for Judo but just before I saw an article about a new Martial Art in town, Aikido. It was a very short article beside a 3¨x 4¨ picture. Right away, I knew that was what I wanted to do, and I registered that afternoon.

克劳德:那时我还在打冰球,但我没有足够的天赋成为职业选手。我哥哥在练跆拳道,所以我也想练跆拳道,或者柔道。我最终决定去练柔道,但就在去之前,看到一篇文章讲当地新来的武术,也就是合气道。这是一篇很短的文章,旁边还有一张3x 4英寸的图片。立刻,我就知道这是我想学的,那天下午我就报名了。

My first class was at a sport center where they had a very good gymnastic program. I was the first one to arrive for the practice, so I entered the room and I stepped on the mat with my shoes and looked through the glass at the gymnastic class below. At that moment, a tall guy entered the room and told me that I should not be on the mat with my shoes. I stepped off the mat and put my gi on thinking that he is going to be mad at me because I stepped on the mat with my shoes on.

我的第一节课是在某个体育中心,那儿有非常好的体操项目。我是第一个来练习的人,所以我进入房间,并且穿着鞋踩在垫子上,透过玻璃看着下面的体操课。那时,一个高个子走进房间,告诉我不应该穿着鞋在垫子上。我走下垫子,穿上我的道服,心想他会生我的气,因为我穿着鞋踩在垫子上。

The tall guy was wearing a hakama, but he was not the instructor. The class began and after the warmups, the tall guy turned around and bowed to me. At that moment, I thought, that’s it, he is mad at me and he will beat me up. Instead, he helped me and made me feel welcome. When a beginner comes to my dojo, I remember that anecdote and I do my best to make the beginner feel comfortable. I ask the same of my students.

那个高个子穿着道袴,但他不是指导员。课开始了,热身后,那个高个子转过身来向我鞠躬。那一刻,我想,他肯定生我的气,会打我的。然而,他帮助了我,让我感到受欢迎。当一个新人来到我的道场时,我会想起这件事,所以我尽力让新人感到舒适。我对我的学生也提出同样的要求。

MAYTT: In 1983, you founded the Centre Métropolitain d’Aikido, and in 1985 you established Aikido de la Montagne. What was one of the major influences for you to begin your own school? Did you find there was something missing in the current aikido landscape and by your doing so, could help fill a void?

MAYTT:1983年,你创立了合气道大都会中心(Centre Métropolitain d’Aikido),1985年,你建立了山之合气道(Aikido de la Montagne)。影响你开办自己道场的主要因素是什么?你是否觉得当时的合气道界缺少了什么,而你可以填补这个空白?

CB: In the early 70s, I had the chance to see Yamada Sensei, Kanai Sensei, and Chiba Sensei while they were in their 30s. Their Aikido amazed me, and I went to all the seminars I could, especially those with Yamada Sensei and Kanai Sensei. I think my instructor at that time was a little concerned with the fact that I loved Kanai Sensei’s style and that I was trying to do many things like him. I always respected my instructor, but I couldn’t resist following Yamada Sensei and Kanai Sensei.

克劳德:在70年代初,我有机会见到山田老师、金井老师和千叶老师,当时他们30多岁。他们的合气道惊艳了我,于是我参加了所有能参加的讲习会,尤其是山田老师和金井老师的讲习会。我觉得我当时指导员有点担心,因为我喜爱金井老师的风格,并且试图像他一样做很多事情。我一直尊重我的指导员,但我忍不住跟随山田老师和金井老师。

Finally, one night we were having a dojo meeting. My instructor was complaining about things that he didn’t like in his dojo. I didn’t agree with him and it was then that I realized that my place was no longer there. After the meeting, I shook his hand and thanked him for all his help over the years. This was not planned, and I didn’t try to bring any of his students with me and that’s probably why I am still on good terms with him.

终于,某晚我们在开道场会议,我的指导员在抱怨道场里他不喜欢的东西。 我不同意他的看法,就在那时我意识到我不该继续留在那里了。 会后,我和他握手,感谢他多年来的所有帮助。 这不是计划好的,我也没有试图带走他的任何学生,这可能是我和他仍然关系良好的原因。

That is how I became a Kanai Sensei student. Twenty-one years later (in 2004), Kanai Sensei gave me the honor of presenting me with the rank of 7th dan and the title of Shihan. I am the only student to whom he gave that honor since he died a few months later.

我就是这样成为金井老师的学生的。二十一年后(2004年),我有幸获金井老师授予7段和师范的头衔。我是唯一一个他授予这一荣誉的学生,他几个月后就逝世了。

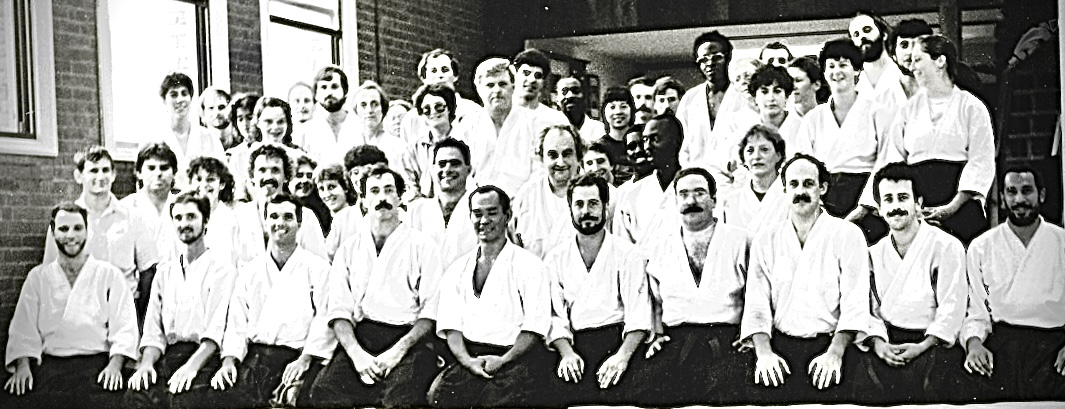

I also have a strong connection with Yamada Sensei who did a lot for me and for whom I have a lot of respect and love, even though my Aikido style looks more like Kanai Sensei. Yamada Sensei brought me to his seminars in Europe and Latin America. Because of that, I made a lot of friends in many of these countries and I still go there on a regular basis.

我也和山田老师有着深厚的联系。他为我做了很多,我非常尊重和爱他,尽管我的合气道风格看起来更像金井老师。山田老师带我去参加他在欧洲和拉美的讲习会。正因为如此,我在许多这些国家交了很多朋友,并且我仍然定期去那些地方。

MAYTT: That is an interesting start for your school. During the 1980s, you forged a connection with Yoshimitsu Yamada and the United States Aikido Federation (USAF). What led to make such a connection and later affiliation?

MAYTT:这对你的道场来说是一个有趣的开始。在20世纪80年代,你与山田嘉光和美国合气道联盟(USAF)建立了联系。是什么促成了这样的联系和后来的隶属关系?

CB: I think that it was a privilege for me to join Yamada Sensei and Kanai Sensei’s organization. Since I was young, they were my role models and I couldn’t see myself anywhere else.

克劳德:我认为能加入山田老师和金井老师的组织对我来说是一种荣幸。从我年轻的时候起,他们就是我的榜样,我无法想见自己去别的地方。

MAYTT: Throughout your aikido career, you had the opportunity to travel and teach at seminars all around the world. In your travels, what do you feel differentiates each region’s or continent’s aikido, i.e., is there a specific focus on philosophy in the United States compared to Germany, or a strong emphasis on flow in the Caribbean compared to Canada? Do different cultures focus on different things within aikido based on your experiences?

MAYTT:在你的合气道生涯中,你有机会在世界各地的讲习会教学。在你的旅行中,你觉得什么区别了每个地区或大陆的合气道,即与德国相比,美国是否有某种特定的哲学关注,或者与加拿大相比,是否加勒比地区更加强调流动?根据的你经验,不同的文化是否关注合气道中的不同事物?

CB: I think that there is a mix of all kinds of people everywhere. Some people like to practice hard, some people like to talk more, etc., but in general, everybody likes to practice and meet after. The more you travel, the more you realize that there are good people and bad people everywhere. I went to places where the facilities were poor, but the heart of the practitioners was bigger than the building.

克劳德:我认为哪儿都有各种各样的人。有些人喜欢努力练习,有些人喜欢说很多话,等等,但总的来说,每个人都喜欢练习,然后社交。你旅行越多,你就越意识到哪儿都有好人和坏人。我去过条件很差的地方,但练习者的心胸比建筑还高大。

MAYTT: From your perspective, how have you seen aikido training transform or evolve since you began? Do you feel that the training has changed, and if so, has it been for the better? Are more proficient practitioners being produced in your opinion?

MAYTT:从你的角度来看,合气道的练习自你开始以来,是如何转变或演变的?你觉得练习发生变化了吗?如果是,它变得更好了吗?在你看来,是否造就了更多熟练的练习者?

CB: I started practicing in 1971 and after one year my first instructor, René Gauvin, stopped training. About ten years after, he came back for a short period of time. He was training like we did ten years before and I could see a big difference between that and what we were doing now. In the beginning of the 1980s, we started to have many more seminars with Yamada Sensei, Kanai Sensei, Chiba Sensei, Tohei (Akira) Sensei and later with Sugano Sensei and Shibata Sensei. These seminars helped many people to improve their knowledge and abilities. I think that the technique of the students now is more powerful and that the postures are also better. Of course, power and posture are not the only aspects of Aikido that we should look at, but they are the easiest to see. Respect, empathy, humility, generosity, self-control – these are important values in Aikido and in Martial Arts in general, but you need closer contact with the person to observe them.

克劳德:我从1971年开始练习,一年后,我的第一任指导员René Gauvin停止了训练。 大约十年后,他回归了很短的一段时间。他就像我们十年前一样训练,我看到这和我们当时所做的有很大的区别。 在20世纪80年代初,我们开始更多地参加山田老师、金井老师、千叶老师、藤平(光)老师的讲习会,以及后来菅野老师和柴田老师的讲习会。 这些讲习会帮助许多人提高了他们的知识和能力。 我认为现在学生们的技术更强大,姿势也更好。 当然,力量和姿势不是合气道中我们应该唯一关注的方面,但它们是最容易看到的。 尊重、同理心、谦逊、慷慨、自律——这些都是合气道和一般武术中的重要价值观,但你需要与人更密切的接触来观察它们。

MAYTT: I see. In addition to training aikido, you train and hold high grades in iaido. From my research, there is a good portion of aikidoka who also study iaido. How did you come to start iaido and why do you think aikidoka take up the practice alongside their aikido training as many have stated that the two arts are somewhat different in movement and stance?

MAYTT:我明白了。除了练习合气道外,你还在练习居合道,并且持有高段位。在我的调查中,有很大一部分合气道练习者也学习居合道。你是如何开始学居合道的?你觉得为什么合气道练习者同时练习居合道和合气道,而许多人说这两种艺术在动作和姿态上有些不同?

CB: Kanai Sensei was doing Iaido and I found it very interesting. I believe that it’s very good for your concentration and posture. Kanai Sensei’s stances are very similar in Iaido and Aikido, especially in the throwing techniques.

克劳德:金井老师练习居合道,而我发觉它非常有趣。我相信这对你的注意力和姿势非常有好处。金井老师的站姿在居合道和合气道中非常相似,特别是在投技方面。

MAYTT: From the entertainment industry to the corporate world, the issue of gender equity still has much ground to cover in our culture, unfortunately. Do you feel the aikido community is immune to such issues in your opinion, especially given the deep philosophical nature of aikido and its teachings? Can aikido training offer a valid solution to such concerns both on and off the mat?

MAYTT:从娱乐圈到企业界,性别平等问题在我们的文化中不幸地仍有很多进步的空间。你认为合气道界对这些问题有免疫力吗,特别是考虑到合气道及其教义的深刻哲学性?合气道锻炼能为垫子上和垫子外的此类问题提供有效的解决方案吗?

CB: I do believe in equity and I do my best to be fair with my students. I don’t ask a student to take care of a class because they are a woman or Black or white or Asian or gay or a trans person. I ask them by rank and if the first one can’t teach, then I ask the next one. All my students can test when they have the correct number of practicing days. Of course, it’s possible to have exceptions. For example, I could ask a female student to take care of a class even if a male student is a higher rank. This could happen if there is no female representation in our group of instructors.

克劳德:我确实相信公平,并且尽最大努力对我的学生公平。我不会因为某个学生是女性、黑人、白人、亚洲人、同性恋或变性人,而让他来授课。我按等级问他们,如果第一位不能教,那么我就问下一位。我所有的学生都可以在练习天数足够时进行考试。当然,也可能有例外。例如,即使男学生的段位更高,我也可能让女学生负责教课。这种情况在我们的指导员中没有女性代表时就会发生。

MAYTT: With being a longtime member and contributor to the aikido community, what are your feelings on the mounting negative views and comments targeted at aikido? Are they truly warranted and, in your opinion, are there things the aikido community can do as a whole to counter or debunk such perceptions?

MAYTT:作为合气道界的长期成员和贡献者,针对合气道的不断增加的负面观点和评论,你有什么看法?它们真的正当吗?在你看来,合气道界作为一个整体可以做些什么来对抗或驳斥这些看法吗?

CB: Because Aikido is a Martial Art, I think that it should involve some efficacy, but this doesn’t mean that we should be invincible.

克劳德:因为合气道是一种武术,我认为它应该多少是有效的,但这并不意味着我们就该是无敌的。

I think that we should have the mentality of a doctor. A doctor does not have the obligation to cure you but they have the obligation to try. I think that every one of us should work on the details that make the techniques works better. Going outside your dojo and participate to seminars is a good way to improve.

我认为我们应该有医生般的心态。 医生没有义务治愈你,但他们有义务救治你。 我认为我们每个人都应该在使技术更好有效的细节上下功夫。 走出你的道场去参加讲习会是进步的好方法。

MAYTT: That is an interesting perspective on that matter. Many dojo feel that the core of their program are those who have been advanced to yudansha standings. However, a program can become stagnant if new students and participants are not joining regularly and make progress. What are your thoughts on a dojo building and maintaining a solid and thriving core of students?

MAYTT:这是一个关于这个问题的有趣观点。许多道场觉得,他们教学的核心是那些晋级有段者排名的人。然而,如果新生和参与者没有定期加入并取得进步,教学可能会停滞不前。你对道场建立和维系坚实且繁茂的核心学生成员有什么看法?

CB: You need all sorts of people in a dojo. Beginners keeps a dojo alive. I always pay attention to beginners and I usually teach the beginners classes in my dojo. I have a program for them and if I am not there, the other instructor follows the same program. I also tell advanced people to practice with beginners. I say the same thing in the seminars that I give. I really like to teach beginners and watch them improve.

克劳德:道场里需要各种各样的人。初学者让道场保持活力。我总是关注初学者,我通常在我的道场上教授初学者课程。我为他们安排了教学计划,如果我不在,另一位指导员会遵循同样的计划。我还告诉高级别学生和初学者一起练习。我在我的讲习会上也说了同样的话。我真的很喜欢教初学者,看着他们进步。